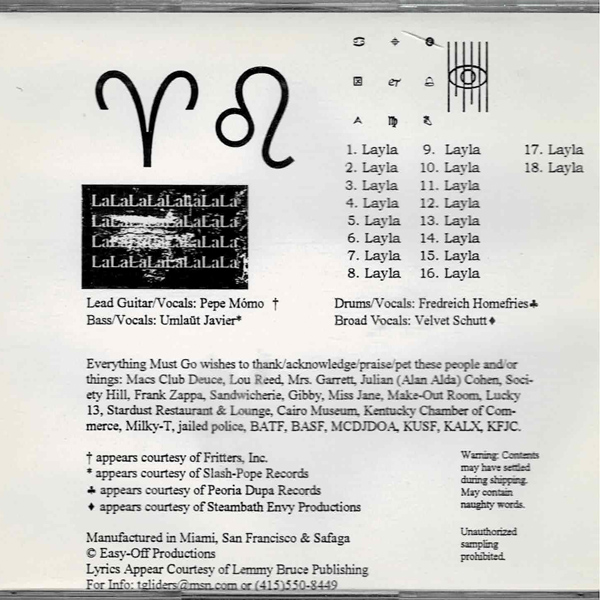

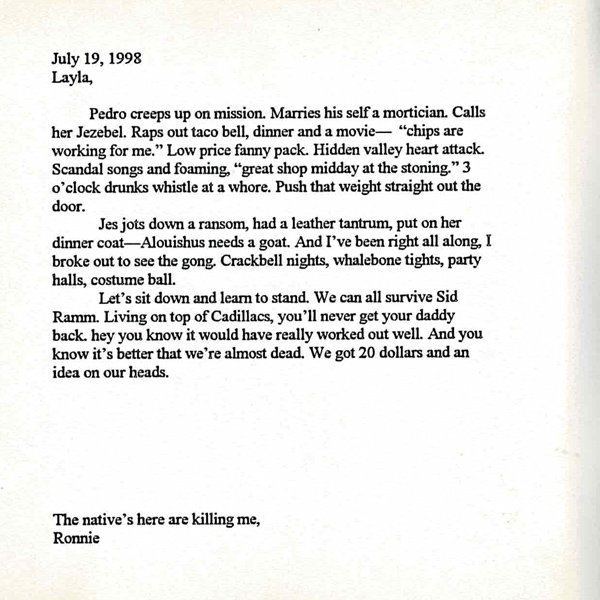

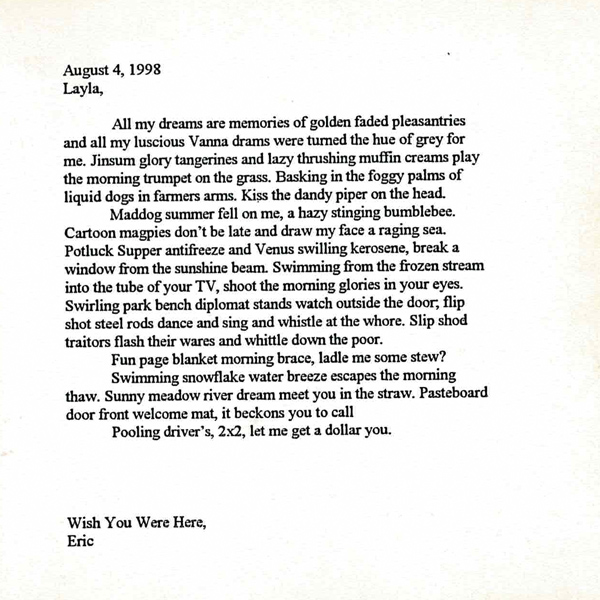

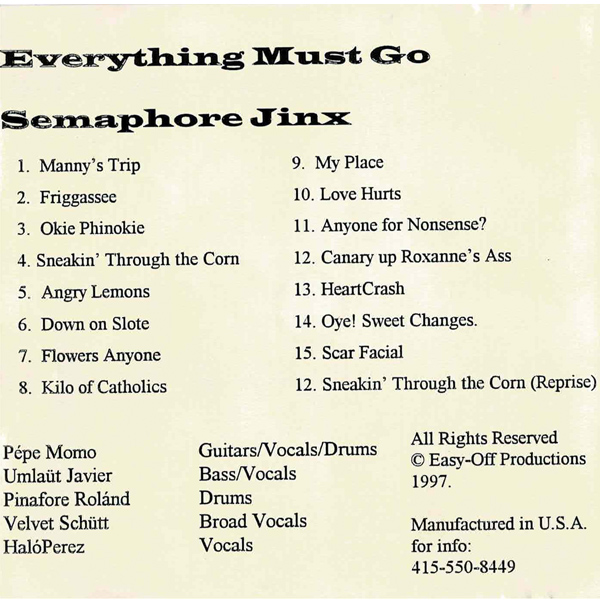

That the Everything Must Go band had its roots in Miami, Florida, this much is true, though there are rumors that much of the album’s self-released eponymous first (?) album were cut in Safaga, Egypt. This cannot be confirmed and seems unlikely. The only suggestion of it comes on the back of the first album, which is surrounded by an abundance of other false or foolish assertions. Crediting production companies that did not exist at the time, for example, and

titling all 18 songs “Layla.” The band operated under a different name in Miami, and there were a few confusing member changes at the time. Musicians joined and left to form other bands, leading to bitter disputes about loyalty and royalties. Curiously, these cessations were not without irony, as each new band weighed in at ¾’s Everything Must Go. Indeed, in Miami, one of the confirmed band names, or new bands, or performing aliases, was The Grand Pequenos, but

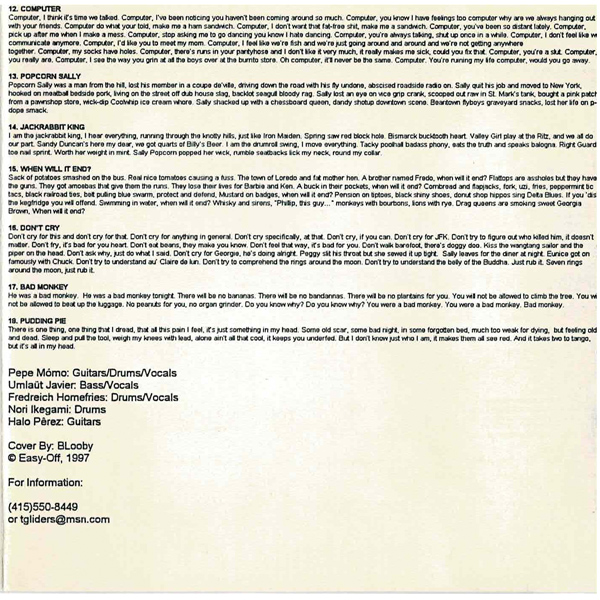

there has been speculation that The Grand Pequenos was simply the name of an Independently released EP, and not the band’s name. As opaque as the band name or names, the names of the group’s members were even more veiled, and most assuredly aliases. Pepe Momo, Umlaut Javier, Friedrich Home Fries, Velvet Schutt, Halo Perez, Nori Ikigami. The only name that can be verified is the latter, though this too, has inspired confusion, as Ikigami insists that he does not know, nor has he ever performed with any of the other band members, or under the name, Everything Must Go.

Shrouded in secrecy, and even at their most extroverted, placing a host of songs on the now-defunct mp3.com, their description was opaque, at best, “Three men of medium height and width,” it read, and, of course, this contradicts the widely held belief that the band included five members, one of whom was a woman.

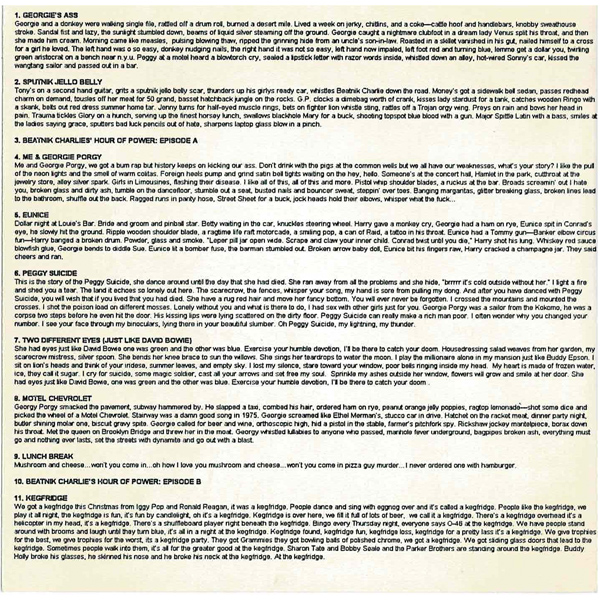

The band emerged from gone and forgotten jungle when a successful adman from Chicago stumbled upon one of their songs in a rack of audio cassettes in the basement of the corporate headquarters. A song that, presumably had been considered, however briefly, for a beer commercial, owing to its name, “Kegfridge.” An odd song called Kegfridge that lacked precussion instruments.

Like the Residents, they donned disguises during public performances, and the only publicity photo ever seen—a rumor, at that—was a black and white of the band standing on their heads with their backs to the camera. An uneven album with songs that ranged in topic and tone from a love affairs with pastry and egg salad to exaltations of simians to musings on submissive and non-submissive anal intercourse. A slanderous opus that couples celebrity males.

Happy Daze was composed by Halo Perez, but reportedly, has not been heard by human ears since 1996. The song, though, only comes up in discussions as it relates to its disappearance. The song is uninspired and lacks substance, lyrics little more than the repetition of character names from the popular 70’s television show, utterances growing steadily more lude and suggestive in tone. This contrasts greatly with the contention that Perez never existed, and was simply an extension of one of the other members stunted libidos.

The majority of their later works were literally put together in a meth kitchen. Javier had temporarily convinced Momo that they needed an album as inspired as Husker Du’s Zen Arcade. Velvet Schutt: Velvet was either the group’s only female member, an accordian player and Umlaut’s girlfriend for a period of several month’s or, perhaps, more probably, a ficticious character, the code name for a pitch adjustment on Momo’s mixing board. One song in particular is highly suggestive.

The song is entitle Computer and the voice is clearly Javier’s, though he seems to be singing with his nostrils pinched shut. Throughout the song he addresses a “Computer,” but seems to be speaking to a lover with lines, more spoken than sung, such as “I’d like you to meet my mom,” and “Don’t ask me to go dancing, you know I hate dancing,” throughout several of the verses. Indeed, Javier did hate dancing, and was often ridiculed by his bandmates on-stage if ever he began to inadvertantly shake his hips in any direction.

Still, while a few engineering choices could turn Javier or Momo’s voice into a falsetto, the songs attributed to Schutt are unlike the rest in tone and texture. Even with the absence of the accordian, the emotion of the lyrics differs greatly from those sung by Momo, Javier, even Homefries. Though, that too, is a possibility. Homefries, whose vocal and creative ranges were always more expansive and melodic than either Javier’s or Momo’s could have conceivably been Schutt.

Umlaut Javier: Umlaut did not become a full member of the band until it reformed in San Francisco, and he severed his ties with the band at Miami in 1996 where drunk and confused, he got in a verbal altercation with his then-girlfriend outside a bar on Alton Rd. She ran into the bar, he drove from the curb to San Francisco, California, leaving his entire estate, and band behind. Little is known about Umlaut’s stormy relationship with the girl, though there are songs in their library that seem to draw from the experience of crossing the country and dating her.

Rumors circulated that Momo left San Francisco for Miami as abruptly as Javier has left Miami for San Francisco. Two suppositions have been circulated. Many of their songs were unlistenable after Arturo’s departure when they began liberally stealing drum tracks from other artist’s records. Jackrabbit King, one of the few songs that features the voices of both San Francisco frontmen, There is some speculation that Arturo was the pseudonym for a drum machine, and this

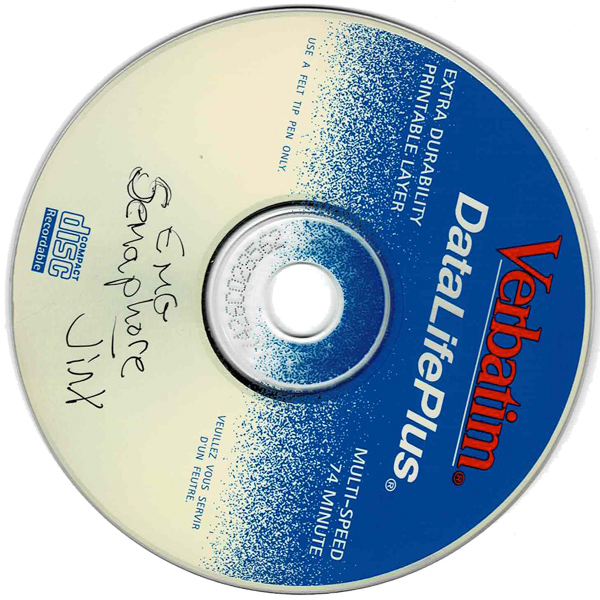

“departure” was a grandiose way of cloaking the fact that it had simply fallen on the floor or had been accidentally smashed to bits. An ex-girlfriend of a former bandmember revealed a piece to the chronological puzzle, suggesting that Semaphore Jinks was the band’s second album, a play on “Sophomore Jinks,” she explained. As well, she suggested that the eponymous album thought to be the first album was more likely, the sixth or seventh release

A pair of songs on the Georgy Porgy concept album have been linked to a gentleman who lived in close proximity to the band in the Mission District of San Francisco, which places the album’s release somewhere in the middle 1990’s. The two songs are, Beatnik Charlie’s Hour of Power: Episode A, and Beatnik Charlie’s Hour of Power: Episode B. In this case, Beatnik Charlie represents a local character called “Cranky Frankie.”

In stark contrast, She Had Eyes Just Like David Bowie (One was Green and the Other was Blue). Still, Semaphore Jinks and the self-titled album do share some commonalities, specifically a couple of mediocre attempts at co-opting rap music into the band’s certainly eclectic repertoire. At one point, Decade, a collection of singles from several of their albums got into the hands of Gloria

Estefan’s people via Ms. Estefan’s hairdresser. Juanita Gray Ellis, one of the “people” at the time, labelled the music categorically “spooky” and never spoke of the band again. The riddle of Velvet Schutt is a curiosity, and is reminiscent, though surely not in a substantive way, of the dreamy alchemical solution that was produced by 4 parts Velvet Underground combining with 1 part Nico

in 1967. Though never a primary member of the band her tracks appear sporadically on at least four of the band’s releases. There were unexplained periods in which certain members of the band fixated on pop-cultural phenomena. The band’s Estimated ETA as well as Happy Daze both seem focused, lyrically in any event on America in the 1950’s, though, more accurately, on the America in the 1950’s as interpreted by prime time TV in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

A defunct San Francisco magazine, Transom, is the source of the only known interview with any member of the band. The reporter who conducted the interview, writing under the pseudonym, Big Sugar Jones (actually the person (sic.) whose words you are currently reading [not confirmed]) caught up with Umlaut Javier in Los Angeles, California in 1998. BSJ: What are you doing now?

Javier: I still don’t get this. What did you say your name was? I’m sick. That’s what I am now. BSJ: Really? Javier: Yes, just put that down. BSJ: I’m terribly sorry to hear that. Javier: It isn’t that great feeling it, either. What? Let’s move on.

BSJ: I wanted to ask you a few questions about your music career. Javier: There was no career. There were no listeners. My girlfriend listened. Since then, other girlfriends have listened. People girlfriends have brought around. Family. Friends, too. Few strangers. I quit the band because the band was gone. There was nothing left for me. Did you ever really listen to any of the music? I

was the weakest link. The only contribution I ever had was lyrics and nobody listened to them. I would play songs for people and they would talk to me while the words were sung. I’d nod quickly so they’d begin paying attention again, but they never did. I could have hummed everything.

The transcript actually continues for another two pages, but that was the end of Javier’s speaking. He hummed the rest of his answers, and Big Sugar Jones ended the interview seconds before he would have been forced to strike the irritating bass player.